Yes of the CGIA to the minimum wage by law, as long as it is measured by the TEC

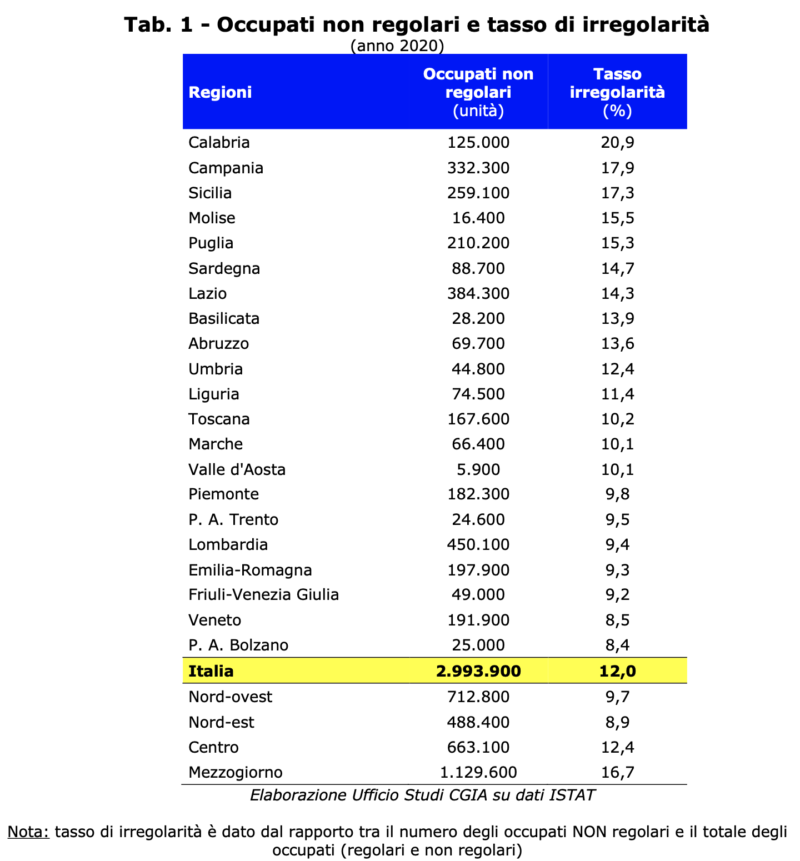

If a minimum wage of 9 euros gross per hour were introduced by law, according to the CGIA there could be a serious danger of seeing an increase in irregular work in the country, particularly in sectors where currently the minimum wages are much lower than the threshold proposed by the bill presented in recent days to the Chamber; these are often sectors "weakened" by a very aggressive unfair competition practiced by the realities that have always worked completely "black". We are talking about agriculture, domestic work and some sectors present in services. In other words, it cannot be excluded that many entrepreneurs, forced to adjust the minimum wages upwards, could be tempted to lay off or reduce the hours of some of their employees, "forcing" them to work anyway, but in " black". The adoption of this "countermeasure" would allow many activities to contain costs and not slip out of the market. At a territorial level, the danger could particularly affect the South which, already today, has a very widespread underground economy, with an incidence that approaches 38 per cent of the total number of irregular workers present in Italy (in absolute terms 1,1 million of people out of a total of 2,9).

Yes to the minimum wage of 9 euros, but if measured with the TEC

Despite this criticality, the CGIA is in any case in favor of the introduction of a minimum hourly wage of 9 euros gross per hour, provided that the items that make up the deferred pay. The latter elements present in the national collective agreement which constitute the so-called total economic treatment (TEC). The accruals of the main items to be added to the MET to obtain the minimum gross hourly wage would be:

- bilaterality;

- fringe benefits (meal vouchers, company car, company mobile phone, vouchers, scholarships, etc.);

- allowance (transfer, night work, holiday work, etc.);

- awards;

- seniority increments;

- thirteenth;

- fourteenth;

- severance pay;

- corporate welfare.

Apprentices are excluded

The latest available data released by Istat show that in Italy there are between 650 and 700 thousand apprentices; i.e. young people hired with an open-ended employment contract aimed at training and youth employment. The duration of the contract varies according to the type of the same: on average it ranges between 3 and 5 years. Furthermore, in general, the monthly salary of an apprentice is around 800 euros net. The amount is low because it responds to the philosophy of this institute which, introduced in 1955, is aimed at under 30s who enter the job market without any work experience and at the end of this path, thanks to the tutoring activity carried out by the company who hosts them, they acquire a profession.

Conversely, the investment made by the entrepreneur is "rewarded" with the possibility of benefiting from a sharp reduction in labor costs. Now, according to data reported by Istat, over 28 percent of all apprentices in Italy (in absolute terms they correspond to almost 205 young people) have a median hourly wage of just under 7 euros. They are employees who in the vast majority of cases have been hired recently; in fact, these apprentices with below-threshold hourly wages have an average number of hours worked lower than about 20 per cent of the more "senior" apprentices who, on the other hand, have a median hourly wage of just over 9,5 euros.

It is clear that if the minimum hourly wage for newly hired apprentices were raised to 9 euros gross, within a few years we would see a drop in the use of this contract. In fact, for companies, hiring a young novice with no experience behind them with an apprenticeship contract would not be more convenient. Also, it should be remembered that with this contract there are many generations of workers who first became excellent skilled workers and then also successful entrepreneurs. Also for these historical and cultural reasons, the institution of apprenticeship must be safeguarded and, therefore, "exempt" from the application of any legal minimum wage of 9 euros per hour.

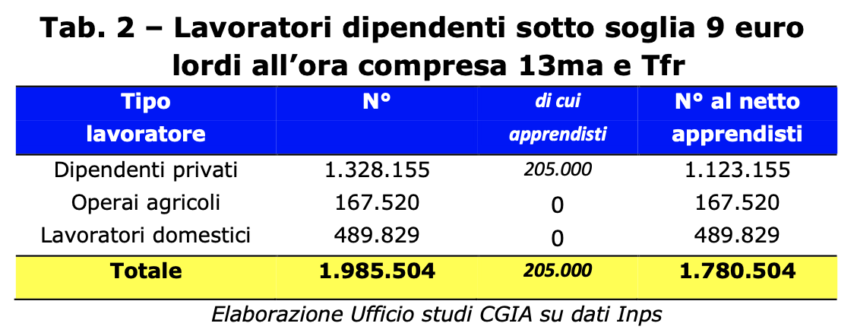

1,8 million workers are affected

The latest available data that can tell us how many workers currently earn less than 9 euros gross per hour are not very recent (2020). Furthermore, we are not even aware of the number of those who, taking the TEC as a "unit of measurement", receive an hourly wage threshold of less than 9 euros. The only source capable of approaching this last "measurement" is INPS; including at the minimum wage (MET) only the accrual of the thirteenth salary and the severance pay, the number of those in Italy who do not meet the minimum wage, as envisaged by the bill presented in recent days by the opposition parties, is 1,9 million . If we subtract the 205 apprentices who in our opinion should not be involved in this measure, the number of "poor" workers is reduced to 1,7 million. It should also be remembered that this figure is certainly overestimated. Firstly because the data refer to three years ago (in the meantime many contracts have been renewed) and secondly due to the fact that the INPS data do not include the economic value of many other elements in addition to the thirteenth and severance pay which, as we have illustrated above, constitute the TEC (bilaterality, fringe benefits, indemnity, fourteenth, bonuses, seniority increments, etc.).

A cost of at least 4,6 billion for businesses

Again according to INPS data extrapolated from the report referred to above, employees affected by the minimum wage by law would enjoy 3,3 billion more income. Businesses, on the other hand, would have to bear an additional cost of at least 4,6 billion, while for the state coffers the increase in wages would lead to an increase in income tax and social security contributions of 1,5 billion euro. These data, however, are underestimated; the amounts just mentioned were estimated by INPS taking as reference a minimum hourly wage of 8 euros.

pros and cons

Net of the risk of undeclared work and the effects on the institution of apprenticeship, there is no doubt that we need to raise wages to guarantee a more dignified standard of living, especially for the weakest workers. From a macroeconomic point of view, for example, with more money in one's pocket it is likely to believe that household consumption would be destined to increase, thus giving an important boost to the economy of the entire country. Furthermore, the state coffers could also count on higher tax and social security revenues. Not only. The specialized literature tells us that low wages lead to a decrease in the commitment and therefore in the efficiency of the workers in the workplace. On the other hand, the adoption of a minimum wage by law would cause a certain increase in costs for companies which, most likely, would be amortized through a consequent increase in the prices of the final products. In doing so, the final consumers would foot the bill.

At the micro level, on the other hand, we must also take into account the drag-and-drop effect that the introduction of the minimum wage by law would have on wage levels which today are above 9 euros gross. It appears clear that, if the salary for the lowest levels were to be raised, the same operation would also have to be carried out for the positions immediately above. Otherwise, many workers would see their wage differential with colleagues hired at lower levels reduced or even eliminated, despite being called upon to perform tasks higher than the latter.

We need to cut taxes and encourage decentralized bargaining

The introduction of a minimum wage by law is not the only solution to make payrolls heavier, especially the lower ones. It would be appropriate, as both the Draghi and Meloni governments have done in part, to reduce the wedge, especially the tax component for employees and contracts should be renewed.

Likewise, decentralized bargaining (ie territorial or corporate) should be encouraged, in such a way as to link additional wage increases to those envisaged by the National Collective Labor Agreement to productivity. We recall that, unfortunately, today only a third of employees in the private sector can benefit from the effects of second-level bargaining.